Wind curtailment in Britain: The rising cost of wasted wind

The past decade has seen a rapid rise in wind farms supplying renewable power to the British grid. Yet, the network is increasingly struggling to distribute this intermittent energy to consumers.

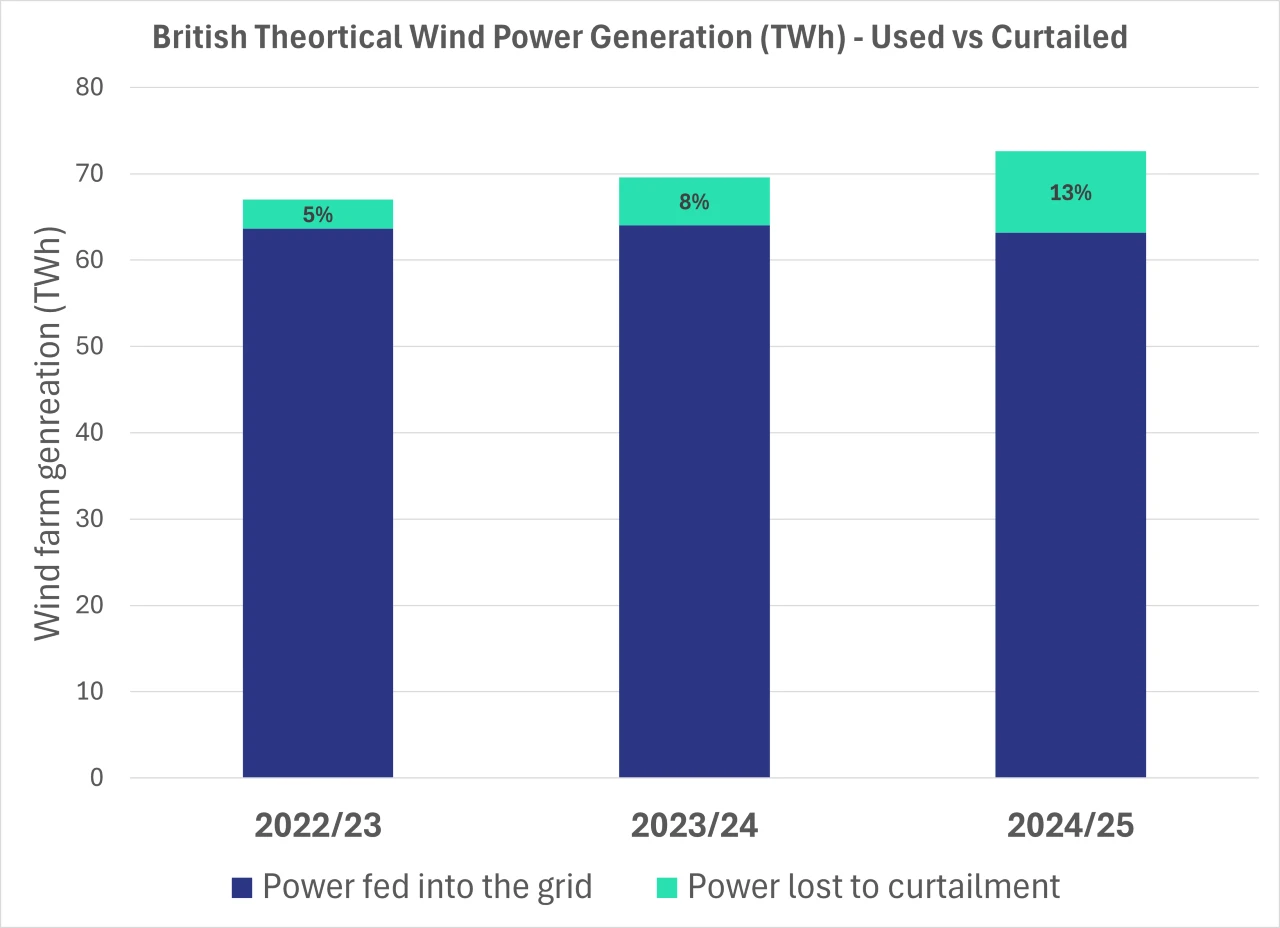

On windy days, the grid in Scotland is frequently overwhelmed, and wind farms are paid to disconnect, wasting their power. Last year, more than 13% of potential British wind power was lost to curtailment, leading to £1 billion in extra costs paid by bill payers.

This guide explains the growing problem of wind curtailment in Britain. Here’s what we cover:

- What is wind curtailment?

- The growing problem of wind curtailment in Britain

- How NESO manages constraints and pays for wind curtailment

- How wind curtailment and balancing costs increase consumer bills

- Electricity superhighways that are designed to fix wind curtailment

What is wind curtailment?

Wind curtailment is when wind farms are instructed to reduce or cease generating electricity, despite being capable of continuing to produce power.

This typically occurs when the high-voltage transmission network reaches its maximum capacity to move electricity from where it is generated to areas of demand where it is consumed.

Curtailment protects the grid from becoming overloaded and helps keep supply and demand in balance. However, the lost renewable power has to be replaced by more expensive generation elsewhere, and wind farm operators must be compensated for the energy they were unable to produce.

The growing problem of wind curtailment in Britain

Electricity losses and the costs linked to wind curtailment have increased sharply in Britain over the past three years.

Data source: NESO – Annual Balancing Costs Report

The vast majority of curtailment comes from wind farms in Scotland, where the grid is highly constrained.

Scotland is home to more than 40% of Britain’s wind capacity, hosting a combination of onshore wind farms in mountainous areas and large-scale offshore wind farms in the North Sea.

On a windy day, these wind farms produce vast amounts of electricity, but due to low population density, there is only a limited amount of demand for this power in Scotland. The transmission network must distribute excess wind power south into England, where it can be consumed.

Limited transfer capacity between England and Scotland

The high-voltage links between Scotland and England do not have enough capacity to consistently distribute all the power generated by wind farms on windy days.

This transmission route between Scotland and England is known as the B6 boundary. NESO models how much power can safely flow across this boundary at any moment. When predicted flows exceed the limit, the system operator must take action to avoid overloading circuits, and that usually means curtailing Scottish wind.

Scottish wind farms suffering curtailment

The grid operator, NESO, publishes data each year showing the curtailment volumes for each wind farm. The latest data show that last year, more than 70% of the curtailment in Britain came from the following seven Scottish wind farms:

| Farm name | Curtailment (MWh) | Approximate cost £m [1] | Capacity (MW) | Type | Location | Theoretical power output (MWh) [2] | Curtailed % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seagreen | 3,626,876 | £459.4m | 1,075 | Offshore | Firth of Forth, Scotland | 5,179,350 | 70% |

| Moray Firth Eastern | 1,639,330 | £207.6m | 950 | Offshore | Moray Firth, Scotland | 4,577,100 | 36% |

| Viking | 768,940 | £97.4m | 443 | Onshore | Shetland, Scotland | 2,134,374 | 36% |

| Dorenell | 334,628 | £42.4m | 117 | Onshore | Moray, Scotland | 563,706 | 59% |

| Stronelairg | 203,638 | £25.8m | 227 | Onshore | Highlands, Scotland | 1,093,686 | 19% |

| Moray West | 186,902 | £23.7m | 882 | Offshore | Moray Firth, Scotland | 4,249,476 | 4% |

| Bhlaraidh | 125,620 | £15.9m | 110 | Onshore | Scottish Highlands | 529,980 | 24% |

| Other wind farms (112 farms) | 2,469,681 | £312.8m | 25,612 | Mixed | Mixed | 123,398,616 | 2% |

Sources: Data compiled using NESO’s BOA data and the Gov.uk Renewable Energy Planning Database and the following calculations:

[1] – Cost calculated using NESO’s reported thermal constraint cost per MWh in 2024/25.

[2] – Calculated using a 55% wind load factor.

Seagreen is currently the biggest contributor to wind curtailment in Britain, managing to deliver only about 30% of its theoretical output to the grid. It is Scotland’s largest offshore wind farm, positioned 27 km off the Angus coast in the North Sea.

How NESO manages constraints and pays for wind curtailment

The National Energy System Operator (NESO) is responsible for keeping Great Britain’s electricity system stable in real time.

To avoid blackouts or damaged infrastructure, the national grid must be kept in perfect balance, with supply matched against demand.

One of NESO’s main balancing tasks is managing the constrained network in Scotland. When wind output is high and the transmission routes are already full, NESO must reduce generation north of the constraint to avoid overloading the lines.

NESO uses the Balancing Mechanism to alleviate the constrained grid as follows:

Balancing Mechanism and power reduction bids

Under the Balancing Mechanism, generators in Scotland continuously submit offers to reduce the power they are feeding onto the grid. These offers, priced in £/MWh of reduced output, indicate the compensation the generator would require for turning down its production.

Wind farms submit these offers because curtailment is a routine part of operating in a constrained network. NESO must be able to call on generators to reduce output at short notice, and the Balancing Mechanism provides a transparent way for generators to state the price at which they are willing to do so.

During times of constraint, NESO strategically accepts these offers in a combination that:

- Reduces flow across the B6 Scotland–England network boundary.

- Maintains local voltage and stability.

Wind farms typically win the Balancing Mechanism auction because disconnecting from the grid is operationally straightforward, and the intermittent power they offer is cheaper than other sources, meaning their lost revenue is lower.

The first element of wind curtailment costs comes from paying the successful curtailment bids in the Balancing Mechanism for each MWh of power the wind farms have not fed into the grid.

Replacing the lost power

Once a wind farm has been curtailed, NESO must immediately replace the lost power by purchasing additional generation in demand centres in England.

Under the same Balancing Mechanism, back-up power sources in England continuously submit offers, in £/MWh, to increase their output to meet any shortfall in power supply.

NESO will strategically accept bids that meet its power shortfall requirements in the cheapest way. The replacement power is typically provided by:

- Gas power stations

- The Drax biomass power station

- Energy storage facilities

- Paid imports from Europe via undersea interconnectors

This is the second, and larger, element of cost in wind curtailment, as these facilities typically require substantial payment per MWh due to the costs they incur to start up on demand and for the fuel they consume during operation.

How wind curtailment and balancing costs increase consumer bills

The costs incurred by the grid operator NESO to curtail wind farms and then make up for their lost generation are ultimately passed on to both domestic and business electricity bills.

The cost of NESO’s Balancing Mechanism payments is recovered through Balancing Services Use of System (BSUoS) charges, which domestic and business energy suppliers must pay for using the grid.

Suppliers pass these charges on to their customers, incorporating them into the unit cost within their tariffs.

Currently, BSUoS charges are 1.496p/kWh, costing the average household £40 a year and contributing approximately 3% to overall business electricity rates.

Why constraint costs are projected to increase without new grid links

The current UK Government’s plan for decarbonising the national grid relies on significant further increases in the capacity of wind farms in Britain.

Renewable planning data from the Government show that there is a substantial pipeline of new wind farm projects planned for Scotland.

| Status | Number of farms | Capacity (MW) |

|---|---|---|

| Operational | 347 | 12,492 |

| Under construction | 39 | 3,380 |

| Planning permission granted, awaiting construction | 144 | 13,509 |

Source: Renewable Energy Planning Database – October 2025

The wind farms under construction and those with granted planning permission will double the current power-generating capacity of Scotland’s wind farms, which will exacerbate the issue of wind curtailment.

NESO’s latest report on balancing costs suggests that today’s annual total of £1.7 billion could rise to between £4 and £8 billion by 2030, depending on how quickly the required transmission upgrades are delivered.

Electricity superhighways that are designed to fix wind curtailment

To alleviate the curtailment of Scottish wind farms and to support the planned construction of additional wind farms, the owners of the transmission networks in Scotland and England are planning significant infrastructure upgrades.

The upgrades include five new subsea routes, known as the Eastern Green Links, which will directly connect the Scottish grid to key demand centres in England.

| Link | Route | Expected operational date |

|---|---|---|

| Eastern Green Link 1 | Torness (East Lothian) → Hawthorn Pit (County Durham) | 2029 |

| Eastern Green Link 2 | Peterhead (Aberdeenshire) → Drax (North Yorkshire) | 2030 |

| Eastern Green Link 3 | Peterhead area → North East England (exact landing point under development) | Early–mid 2030s |

| Eastern Green Link 4 | Fife / East Scotland → Norfolk (East of England) | Early–mid 2030s |

| Eastern Green Link 5 | East Scotland → East England (route still in early development) | Post-2035 (TBC) |

The construction of these new high-capacity electricity transmission routes is a key component of the Great Grid Upgrade, a nationwide plan for transmission network upgrades.

The transmission network upgrades are initially funded by the private owners of the transmission network, but will ultimately be passed on to consumers through increased Transmission Network Use of System charges.

Central planning for Britain’s renewables

The rise in wind curtailment is closely linked to the economic incentives that shape the privatised energy sector.

Wind farm development in the UK has been strongly supported through the Renewable Obligation and Contracts for Difference schemes, but these incentives did not guide where new projects should be located.

As a result, many wind farms were developed in Scotland, Britain’s windiest region, without consideration for whether the existing transmission network could reliably move that power to where it was needed.

At the Government’s direction, NESO is developing a Strategic Spatial Energy Plan, under which future subsidies will prioritise the development of renewables in locations that place the least strain on the existing grid, reducing the need for wind curtailment.

Policy options for wind curtailment costs

The fact that wind curtailment costs Britain’s electricity consumers over a billion pounds each year causes considerable public anger.

Wind curtailment is not a failure of renewable energy, but a symptom of a grid that has not yet caught up with the pace of decarbonisation.

The majority of the cost comes not from paying wind farms to switch off, but from paying other generators to switch on elsewhere because the transmission network cannot move power efficiently across the country.

Until new electricity superhighways are delivered and more grid flexibility is built into the system, curtailment will remain part of how the grid is kept secure.

In the meantime, the proposals below outline the different ways the burden of these costs could be shifted to other areas of the energy industry.

Locational Marginal Pricing

Under the Locational Marginal Pricing plan, prices in the wholesale electricity market would vary by region, reflecting local grid congestion conditions.

Under this approach, electricity prices in Scotland would fall because supply exceeds local demand. Wind farms in Scotland would therefore earn lower prices for their output, reducing the incentive to develop additional projects in the region.

Enacting this plan would likely be highly controversial, as it would result in significantly higher prices for consumers in demand-heavy areas in south-east England.

Variable grid access charges

Some other European countries use a system in which generators are charged a variable amount for the right to inject power into the grid.

Under this system, generators are charged if the electricity they produce causes congestion on the grid. This provides a direct incentive for wind farms to be built in areas that have more grid capacity.

Network operators paying for wind curtailment

A further idea is one in which the transmission network operators pay for any curtailment that occurs on their grid.

In Britain, the transmission network is owned by:

- National Grid Electricity Transmission – England and Wales

- Scottish Power – Southern Scotland

- SSE – Northern Scotland

Under this plan, curtailment costs would penalise these network operators, providing a financial incentive to upgrade their networks to address these issues.